Note: There were no In-class Activities for Sessions 1–4, 7–8, 10–11, 13–21, and 23–26.

Session 5: Identifying rhetorical appeals

- Each group shares the purpose and target audience of the articles, using evidence to support their claims: word choice, definitions, naming conventions, organization, and negative space (i.e. information not included in the article).

- Each group is assigned one text—“3-D Printer Saves Toddler Struggling to Breathe,” “Deadly Contact” (written text only), and “Deadly Contact” (images and captions only)—and identifies examples of logos, then shares their findings with the class.

- Each group is assigned a different text and identifies examples of pathos.

- Each group is assigned a different text and identifies examples of ethos.

Session 6: Constraints and opportunities in genre

- The chalkboard is divided up into three parts (one for each assigned article).

- The class lists as much as information as possible about the target audience(s) and genre of each article.

- Students list the characteristics of the form each article, as well as any communication constraints and opportunities within each genre.

- As a class, we move through each list and make any final additions, and then look at all three lists to discuss both differences and similarities of audience and genre (form, constraints, and opportunities).

- Students discuss the choices each writer made to communicate effectively in each genre.

Session 9: Transparent Stories with Citations

Session 12: Translating a journal article for the public

In-class activity 1: Naming conventions

- Students are shown the technical language from the peer-reviewed article ("Music in Everymind: Commonality of Involuntary Musical Imagery" (PDF)) that informs the content of the lay-friendly article, “Why Do Songs Get Stuck In Our Heads.”

- We discuss the implications of the choice to use the term “earworm” as the dominant metaphor through “Why Do Songs Get Stuck In Our Heads.”

- Students read sections of “Why Do Songs Get Stuck In Our Heads” to detect Gopen and Swan’s sentence structure, in which the known subject is introduced before the unknown/new information/subject.

In-class activity 2: Topic sentences

- The class reads aloud every topic sentence from the article, “Why Do Songs Get Stuck In Our Heads.”

- Students identify the claims made in each topic sentence, and then scan the corresponding paragraphs to determine whether the content of each paragraph directly relates to the topic sentence, or whether the paragraph content differs from topic sentence.

- Students then scan the topic sentences of their draft articles.

- Each student reads one of their topic sentences aloud to a classmate, and asks them to share what they expect the rest of the paragraph to discuss, in order to determine whether there is alignment between their topic sentences and paragraphs.

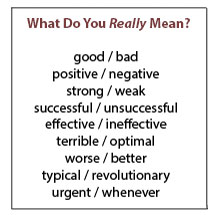

In-class activity 3: Making imprecise subjective language more precise

Students circle instances of vague nouns (e.g. "it" and "that") and subjective adjectives (e.g. "good" and "bad") in their own drafts, and then replace these words with more precise language.

Session 22

- Are there any larger moral, political, philosophical, or economic issues that surround your narrow topic?

- Do you have a genuine sense of wonder or fascination with your topic, or an aspect of your topic? If so, how might you communicate that to the reader?

Session 27: Final Class Reflection

- What is one piece of advice you would give to an aspiring science writer for the public?

- What knowledge can you take with you from this class for your future classes and professional work beyond college?

- What is an aspect of your communication (writing/speaking) that you have improved this term?

- What is one aspect of your communication that you want to continue improving?